going home

Jonathan Chan (b. 1996)

i run in the enfolding of sunset. street

lamps burst into electric luminosity, just

as pink seeps through the cracks of cloud

cover. the darkness does not overcome

the light, though it envelops the cradling

of hope. absence yields the breath of

possibility, however long the stretch of

dusk. the streets begin to hollow, craters

filled, drains cleared, and craftsmen ferried

home. my feet carry me into the evening.

each room’s sliver of light goes off: the

aunties’ video chats at the sharp corner

of our staircase, the blue blade beneath my

father’s room, and the rush of my own

vanishing bulbs. away in tuas, shrouded

in the dark by towels draped on metal

frames, brothers pray by the glow of

smartphone screens.

and so do i.

(2020)

***

John 1:1-5 (NIV)

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was with God in the beginning. Through him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made. In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

***

***

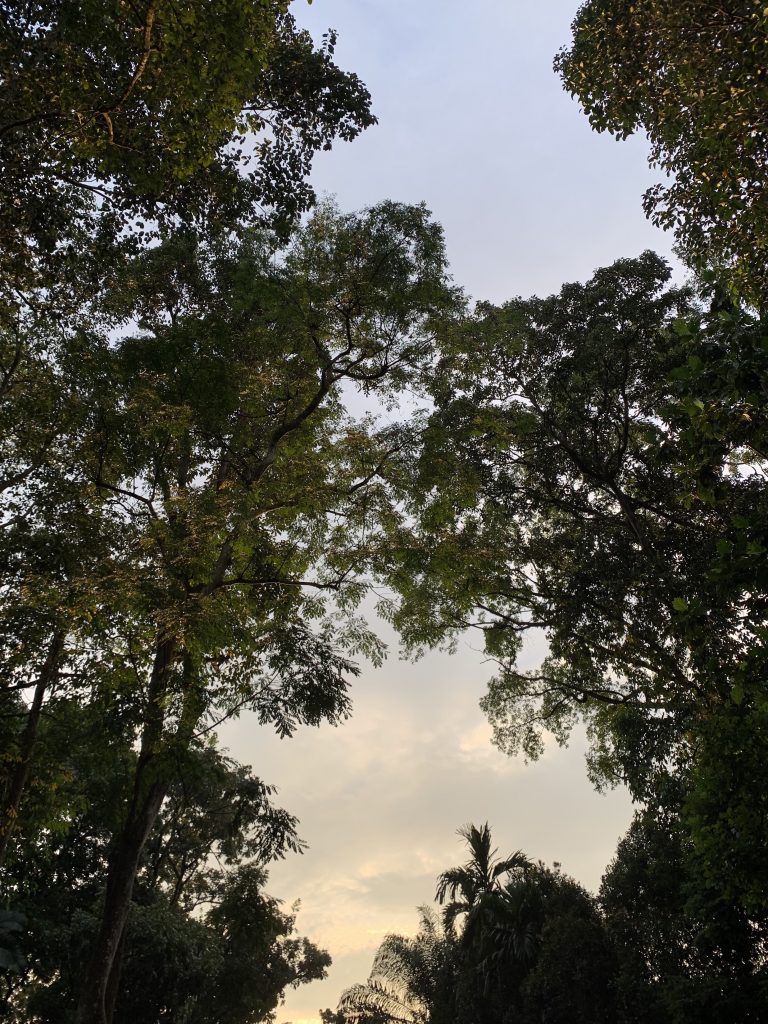

I wrote this poem several months ago in Singapore. I was out for a run late in the evening and found myself caught in the moment between day and night as the sun was setting and the sky was painted over in a brilliant swathe of colours: blue, pink, and orange. As I ran my usual route around my neighbourhood, I listened to an interview with Rebecca Solnit on the On Being podcast. Solnit has written widely about reconciliation and grief in the aftermath of disaster, and her conversation with Krista Tippet touched on her experience documenting the fallout of Hurricane Katrina as well as how disasters clarify a sense of attention to the present. She mentioned that it gives people ‘this supersaturated immediacy that also includes a deep sense of connection.’ At the time, I had just completed an internship with HealthServe, a non-profit providing casework and medical assistance to migrant workers, and as a consequence was also beginning to pay attention to the migrant brothers in my neighbourhood, ferried in and out by lorries each day to work on new homes.

All of this – the sunset, the podcast, the roadworks that bore the absence of the workers – began to coalesce in a poem when Solnit and Tippet began to speak about her book, Hope in the Dark (2004). In Solnit’s own words, she wrote the book, ‘to rescue darkness from the pejoratives, because it’s also associated with dark-skinned people, and those pejoratives often become racial in ways that I find problematic.’ She elaborated that this hope is where darkness is ‘the future’ and where

‘the present and past are daylight, and the future is night. But in that darkness is a kind of mysterious, erotic, enveloping sense of possibility and communion. Love is made in the dark as often as not. And then to recognize that unknowability as fertile, as rich as the womb rather than the tomb in some sense. And so much for me of hope is, as I was saying, not optimism that everything will be fine, but that we don’t know what will happen.’

There was a particularly biblical bend to her language as she spoke of darkness as the crucible of hope and possibility, an enveloping sensation that stirs new imaginings and yearnings.

I thought of St. John of the Cross and the periods of lament and estrangement from God we are all wont to experience, but also of the simplicity of the beginning of John’s Gospel: that in Christ was life, that this life was the light of all mankind, and that the light has overcome the darkness. It hummed in my mind like a mantra as I thought of the darkness that envelops us as we go home, whether for myself, my family, the domestic helpers who live with us, the migrant workers living in dorms, and how it augurs not despair, but hope, resilience, and possibility.

When we dwell in the darkness and remember who God has been and will be, does it help us to find hope?

***

© 2020 Jonathan Chan