Christopher Tan (b. 1972) is a writer, cooking instructor, and photographer. A commentator on and chronicler of food, culture and heritage for local and international publications for over two decades, he has given talks and demonstrations at museums and symposia in Singapore, Paris, California, and Sydney. He has authored and co-authored numerous cookbooks, most recently The Way of Kueh, a compendium of Singapore’s traditional kueh heritage which won Best Illustrated Non-Fiction Book and Book of the Year at the 2020 Singapore Book Awards.

In this interview, Jonathan and Christopher talk about Christopher’s path to becoming a writer, a theology of cooking and eating, and the sense of the ineffable that has carried Christopher through his work.

***

Jonathan: Was there a spiritual or religious element to your upbringing? I’m thinking particularly of how you grew up between the UK and Singapore – how did these transitions and this exposure to different places and communities shape you?

Christopher: On religion, not at all – my immediate family were not even faintly religious. The first time I had any taste of organised religion was after my parents and I moved to the UK when I was 13. I enrolled in a local school that was nominally affiliated with the Church of England – we sang a hymn in assembly twice a week, and Scripture was a subject at the primary level. The latter had much less of an impact on me than the influence of Christians who were my form teachers and mentors during my secondary and high school years.

One other thing which opened my eyes to religion – which I am not at all being flippant about – was that in the UK I lived not far from a predominantly Jewish area whose shops were the only ones open on Sundays in the ‘80s. So one of the first things which acquainted me with the people of the Book was their food and the importance of food in their culture… and also how ingrained their religion was in their everyday lives.

In hindsight, I think God was speaking me to during my childhood and teenage years through what C. S. Lewis has identified as ‘sehnsucht’ – the longing for something ineffable and indescribable but yet that was intensely craved. One clear moment of this happened when I was in France on a school history trip, and wandering around Bayeux Cathedral in Normandy… I had not spent much (if any) time in churches before then, and the ambient mood of the cathedral just seemed so different to me, somehow elevated and separated from regular everyday life. I reckon this was not so much because of anything particular about the setting, but because God was allowing me to sense something of His presence, to the extent that I could at that stage of my spiritual development.

Reading English children’s classics in my youth, by C. S. Lewis and his ilk, exposed me to a certain metaphysical-mystical-magical realist strain of storytelling which likely primed me for sehnsucht, also. I am thinking here of authors like Lucy M. Boston, Alan Garner, Susan Cooper, Lewis Carroll, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Richard Adams, and such.

I actually came to Christ after a platoon mate witnessed to me during BMT. Shortly after this, I started attending a local church. Then, after finishing NS and going back to the UK for university – ironically enough, UCL, the ‘godless college’ – my experience of the faith exploded after I joined the Christian Union and a gospel choir, visited churches of different denominations, attended Christian festival camps, and so on.

Jonathan: That sense of the ineffable, this sehnsucht that Lewis identified, is such a profound and transcendent sensation. It must have carried you onward after university, as you transitioned from your academic training in psychology to your present endeavours in writing about food. How did God bring you along this path?

Christopher: When I was in primary school, I felt drawn toward the craft of writing, albeit in a vague and inchoate way. At the secondary and high school level, I opted for science rather than arts subjects, as they interested me more, and also out of pragmatism – this was in an era where the arts were not as prominently supported in Singapore as they are now. In university, psychology was the only subject I felt suited me. It also taught me valuable skills – the rigour and concision of writing papers, planning analyses, and experimental trials – which serve me to this day.

After graduation and trying and failing to find a job in academic research, I ended up working for a magazine publisher, writing mental health articles for its health magazine and food articles for its F&B mag. Gradually, food writing subsumed all other endeavours. After I left that firm to go freelance, I started writing cookbooks as well as teaching cooking classes, and have been doing that ever since.

Something which God has always impressed on me – and I mean on me personally, I don’t mean to say that this is necessarily prescriptive for anyone else – is that my responsibility is to look after my character and spiritual formation and that God’s responsibility is to look after my reputation and career. And He holds me to it – I can testify that every single attempt I’ve made to further myself by making connections with influential people or ‘bigging up’ my work has failed, often dismally so. Only when I take the hands off the reins and leave it to God to open doors and nudge me in the right direction and fill my creative lamp with oil, that’s when things fall into place. God takes all the credit.

Jonathan: That’s incredibly encouraging – and quite sagely counsel for so many involved in creative pursuits, whether it’s meant to be prescriptive or not. Though thinking of food, while it may often be overlooked, food is central to so many pivotal moments in the Bible – feasts, celebrations, weddings, harvests. Even recipes feature in some chapters of the Bible. What have been ways you have been able to weave some of these Biblical notions and representations of food into your creative work?

Christopher: The first ‘recipes’ in the Bible are actually for anointing oil and incense, dictated to Moses by God in Exodus 30. God very firmly instructs him that the oil and incense were sacred, holy things not to be used frivolously or merely for sensory pleasure – they were signs and carriers of holiness itself. The incense is also twice referred to as ‘the work of a perfumer’ – and yet, how often does perfumery feature in modern-day surveys of ‘Christian art’? Clearly, God cares about smells. I originally started thinking about all this when I had the opportunity to write a couple of pieces about the intersection of food and perfumery and the immense complexity of natural aromas.

Also, a central thread of my book The Way of Kueh (2019) was to encourage people to rediscover the meaningfulness and fruitfulness of cooking together with their families, extended families and communities – to understand that it not only eases physical labour and produces wonderful food but also that it strengthens bonds and passes on wisdom and legacies.

Most people, in the church and outside of it, seldom think of cooking as ‘art’ unless it’s in the context of high-concept fine-dining, or decorated cakes, to be honest, and they can be dismissive, whether consciously or not. I get strangers asking me for free recipes now and then – I’m not sure if they realise that as a cookbook author and culinary instructor, I invest a lot of time (sometimes years), effort and expense in recipe development, and that’s how I make my living. I always want to reply by asking them if they ask doctors they barely know for free prescriptions, but I bite my tongue…

Jonathan: It’s such a restorative act to reframe cooking as a fundamentally communal activity, and a sensuous, visceral one as well. There’s something about the sensations, smells, and tastes that can bypass the rational or intellectual and bring people into a fold of warmth and affection. There’s something about how a recipe transmits memory, one that is both embedded and embodied through the shared acts of cooking and eating. Is this part of a holistic vision that you’ve attempted to put forth in your work?

Christopher: I believe that insofar as the Fall corrupted mankind, it is echoed in how our desires and drives – created for and meant to be directed towards good things – get led astray. Greed and lust are corruptions of good desires for things meant to nourish and help us physically and spiritually, warped into never-satiated hunger for unhealthy amounts of unhealthy things.

Hence in all aspects of my work, I feel pressure to help point and guide others in the opposite direction, to help them rightly perceive and rightly respond to themselves and the world, the flesh and the spirit, the beautiful and the ugly.

Secular art – and increasingly, the contents of social media platforms such as TikTok and Instagram – is made and positioned to glorify itself or the cleverness of the artist who created it. As Christians, we have a different mandate – we use our art to point away from ourselves and to God and the things of God. And yes, to foster sehnsuct.

Also, I view cooking as an incredibly unique discipline: cooking is both a craft and an art form. It is also one of the most necessary crafts and art forms – we all need to eat. It is also one of the most accessible and easiest to acquire skills – learning to cook at a decent level is easier than, say, picking up piano-playing, I would argue. As a medium, food is as capable as music or dance or prose at expressing all aspects of the human condition and experience, and at evoking emotion: we can often lose sight of this because of cooking’s everydayness.

Learning to appreciate ingredients, from the agricultural level upwards, is part of creation care, and cooking and eating wisely is an inseparable part of care for oneself and others, and also of medical ministry. Cooks and farmers receive and engage with the food-related symbols and metaphors in the Bible – salt, yeast, wheat, harvest, fruit, etc – on a different level than non-cooks and non-farmers, simply because we live and work close to the ground.

In the context of the wider Church, making food to bless people has always been a core part of my role in the various ministry groups I’ve been a part of. So I guess my culinary creative impulse has served more of a ‘tentmaker’ type of purpose rather than through an overtly ‘artistic’ contribution. I probably enjoy it more this way.

Yet beyond once writing a few recipes for a church magazine, and cooking for the odd bake sale or pot luck, my food work has not directly impinged on my organised church life. Perhaps the only – and the most vivid – exception was when on a couple of occasions I was roped in by a friend to help put together and lead Messianic Jewish Passover dinners with liturgies for small groups, which were enormously fulfilling and meaningful endeavours for me.

With regard to food embodying memory and meaning: Jesus instituted holy communion as an act of eating and drinking and remembrance, and did so in the context of a supper. Then, among Jesus’ first recorded post-resurrection deeds, he cooked a barbecued fish breakfast for the disciples. What does all this say about the significance of cooking and eating together in the new kingdom?

Jonathan: That’s an incredible way of weaving together all these dimensions of the act of cooking, whether symbolic, scientific, or communal. Were you ever conscious of the relationship between your faith, your work, your cooking, and your writing, the latter two particularly as artistic practices?

Christopher: I find these questions quite tough to answer. I have always tackled the writing first and foremost from the posture of a jobbing writer – 2 Thessalonians 3:10, after all – as opposed to from an identity as ‘an artist’.

For even when we were with you, we gave you this rule: “The one who is unwilling to work shall not eat.” (2 Thessalonians 3:10, NIV)

I focus on and enjoy the craft of writing without feeling I need to wear a hat that says ‘artist’. It’s more like – these are the skills I’ve been given and been enabled to nurture. Therefore these are what I use to make my way in the world and make my living. In fact, it was probably only when I started attending meetings with The Group in its early days that it even occurred to me to think about writing as my ‘artistic practice’. It still doesn’t feel wholly natural to me to come at it from that angle.

Music is in many ways, my first love. I can’t play any instruments or write songs, but I love singing. As mentioned, I was in a gospel choir at university for 3 years, and in a Christian a cappella group in Singapore, Agapella, for 12 years. I find the immediacy and intimacy of live vocal performance simultaneously dauntingly challenging and enormously thrilling. Among the hardest and also most rewarding experiences in my life thus far have been the album recordings I did with Agapella and for some other ministries. I’m not currently involved in any music ministries, and I miss it sorely – it’s like not using a limb.

And then there’s photography: I initially got into it from having to take my own photos for journalism work assignments. From there, I segued into becoming a weekend hobby photographer, to doing wedding shoots for friends, to finally shooting all the photographs for my own cookbooks.

When I really think about it, the work projects which I most enjoy and which seem to be the most fruitful are those which require me to wear multiple hats simultaneously. When I teach cooking, I draw upon my writing skills to craft detailed recipes, as well as upon my performance skills during the actual class. I use both of those skills, plus photography when I give talks and presentations with slideshows and demonstrations. I draw on my science background when I am researching and developing recipes for my cookbooks, and then on my academic and journalist experience to digest and translate the information into palatable forms (in all senses) for readers.

It has been a gradual realisation for me that perhaps I am called to work the boundaries – to inhabit the spaces and bridges between disciplines and fields, to have feet in different camps and fingers in different pies. I’m figuring it out as I go along.

Jonathan: To kind of stalk the borders, or to probe the boundaries between disciplines – that’s such a vital role to be playing.

Now, what would you want to say to pastors and ordinary church folks who may not be familiar with your writing as a form of art, or even with food and cooking as a mode of worship? I’m thinking of how occasions such as Christmas or the Lunar New Year are ripe with opportunities to get people thinking about a theology of food.

Christopher: What a great question. I think Robert Farrar Capon’s The Supper of the Lamb (1969) covers pretty much all the bases with regard to a theology of food – I would recommend that to them, first of all.

Second of all, I would point to a Feast as being both a frequent biblical metaphor and an explicit feature of the coming kingdom as mentioned by Jesus himself, and ask – how can our feasting on earth now prefigure and anticipate the Feast?

Who are the ‘widows and orphans’ and Mephibosheth-es whom we can host and serve? Can we leave aside lame jokes about ‘fei lo ship’ and view our dining tables as opportunities to proclaim and practise the kingdom?

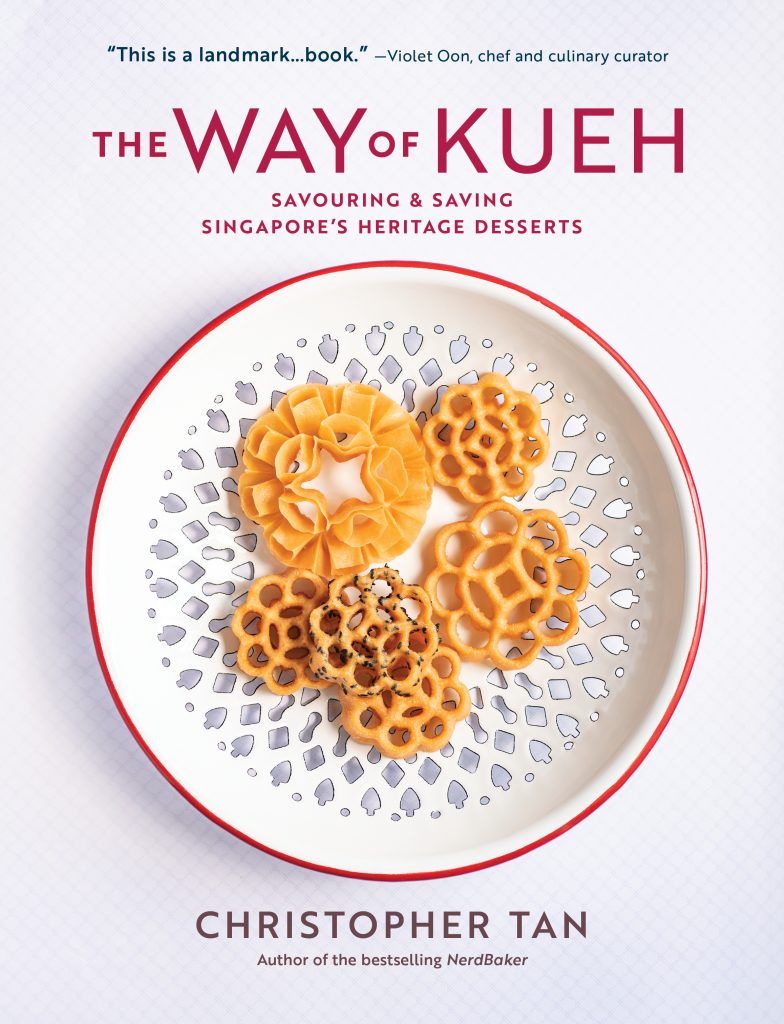

Cover image: ‘Matthew 19:14’ by Christopher Tan

Website: http://foodfella.com/