David Wong Hsien Ming discovered poetry as a child at a Sunday lunch. His work explores the dualities, contradictions and absurdities of being, and has appeared on platforms like Quarterly Literary Review Singapore and Mascara Literary Review. His first collection, For the End Comes Reaching, is a meditation on the sense of loss that accompanies each having.

In this interview, Jonathan and David discuss the beginnings of his journey in poetry, the compulsions and techniques that inform his work, and the place he sees himself occupying in the community of the Christian faith.

***

Jonathan: The first question I have is the question of whether there’s a spiritual or religious element to your upbringing.

David: I’m definitely born and bred in the church in a sense. My family literally attended the same church most of my life. It’s kind of like a community church – Yio Chu Kang Chapel – that sprung out of the Brethren network. My Dad was an elder in his later years. I think most of his work was maybe in tone and culture in terms of fundamentally being a joyful, listening, comforting kind of presence. It was very much, as with a lot of these service-related roles, where I thought the good of what he brought as a person within our family, he then had to essentially bring that out for the whole congregation.

What was cool was that it showed me that being performative makes it no less honest and no less valuable. Even in my job as a teacher now, there’s clearly a performative element, right? Even when I get angry at students, it actually performative. It’s bad when it’s actual anger. If you’re not sincere in every single situation, but you’re always cognisant of the performative element and you’re always there for a person, I think the totality of that work will affect someone in terms of a spirit of compassion.

And then my Mum was pretty much the opposite. She was much more private. There were particular sorts who would be as withdrawn as she is, and she would become that anchor for this subsection of people. Not that they didn’t fit in at church, but they would need a very particular sort of confidant. In terms of that community element of church and the practice of spirituality, that’s probably what I picked up over the years.

***

Jonathan: My next question is kind of tied to that because you wrote in your bio that you discovered poetry as a child at a Sunday lunch. That recurs frequently in some of the bios of yours I’ve seen.

David: Oh yeah, it’s like a default thing to chuck in. If you’re someone that bothers to read bios, just throw them a bone. I’m not going to bore you too much with too many high-minded aesthetic aspirations.

That incident was more just a moment of like, I don’t know, spitballing, and I just wrote this tiny, really shitty poem and then my Dad was so proud of it, he printed it and put it in a laminated thing and then pasted it in his office. And then after that, I didn’t write for three years because I hated it. It was like, my gosh, if you’re proud of that… I’m not gonna give you more stuff to paste up if it’s of that quality. So not that it was bad. It wasn’t a bad experience. I just knew that was a crappy poem.

Jonathan: Was there something that just compelled you during that lunch?

David: I am a Christian that struggles to maybe notice when there are things like calling or phenomena that we might call blessing. I think for the most part I do believe in their existence.

I think maybe for me, when it is so mundane and disconnected from any form of causality, that’s ultimately some of the most authentically spiritual experience. I think that for someone like me, it’s really, really comforting. It really feels like the closest someone like me can get to being spoken to when it comes from so far out of left field. I think to some degree if God were to throw me a bone, that’s what the Lord or the Holy Spirit would see as some sort of mercy upon the individual that I am because otherwise, it would be very hard for me to declare I believe.

I could be in a church service environment where there’s like gold flakes falling in the sky and people doing whatever and I would be like, ‘Okay’. It wouldn’t move me in any way. But I think that kind of incredibly mundane situation is what really gets to me.

So, maybe that’s a real gift. Maybe it’s a temporary gift, but you nevertheless can see that as a bit of a gift.

Jonathan: Do you think that, both this way that you think about a divine occurrence occurs in your life, how this character of God has been visible in your life through this mundanity, that these have seeped into how you write your poems?

David: I’m in a bit of an in-between phase. I don’t really know what my current or new writing is moving towards or what it will congeal into, but I think it probably informs my love for images. I have a bad habit of moving between images too much and too rapidly. The way I spin out something fantastical or bizarre or like the way I abstract images, I guess that would help. The mundanity is usually like the starting point. I think what I want to do, and I think to some degree yourself as well is, that if we are abstracting images or something concrete, that’s maybe more towards like theme or feeling or moment. That’s probably one of the major goals of my writing.

***

Birthday Party

David Wong Hsien Ming

We thank the Lord for making this day.

What a cop-out. Like thanking the cheap lighters

for flames we persuaded onto candles ourselves.

Faith that is careful ignorance; finding grace

in miracles we forgot we wrote; taking dreams

to be anything but the quiet work

of synapses.

Still, we pour love

into the ghost possibility.

Not because the illusion of salvation

is salvation enough. Because

it has already been tasted,

however unevenly. Even here,

in the silence of conceding wax,

in each blackened wick

that proves each of these nine years–

I watch sheets of ice hug themselves into continents

above the fruit punch. Is this you, Lord,

waiting to break it all?

***

Jonathan: Was there an undercurrent of poetry when you were growing up?

David: One of the fun things in my journey is that I dropped lit in secondary school. I kept reading, obviously, but that’s the best part, right? The House of Sixty Fathers kind of broke me. It’s not a bad book, but that was our text and I was not a fan. I wasn’t in GEP at the time and they were doing The Restaurant at the End of the Universe and much more fun stuff. So, jealousy kind of set in and I said, okay, forget it. Then I was mostly in science, actually, until I did philosophy in university.

I don’t think I was ever like majorly into a poetic canon. I was probably more of a fantasy, sci-fi kind of person and poetry was on and off. Around JC, I guess the switch was turned on. That’s why I’m always happy to be associated with The Group because a lot of my reading of poetry started with Ronald and me exchanging stuff to read together, writing a bit here and there.

Jonathan: Do you remember who you were reading in that formative period, both on the science fiction side and also the people you were absorbing via Ronald?

David: Sci-fi in that roughly three to four-year range would be like Asimov, who I’m still a big fan of, with the Foundation series that spans several millennia is about the nature and trajectory of a planet or the human race. It had an essentially bizarre ending in some sort of unified, beauty-focused gestalt mind state. That was pretty fascinating.

In terms of the poets, Gerard Manley Hopkins, who wrote a lot about Christianity and spirituality and madness. A lot of e. e. cummings, that kind of classic Anglo canon. And then you graduate to slightly more contemporary stuff like the playfulness of Kay Ryan. For me, when I eventually went off my own, I absorbed a lot of the contemporary modern American kind of canon.

Jonathan: I remember reading your essay on Denise Levertov as well.

David: Oh yeah! Levertov of course. It was Levertov and Hopkins. What I got from Hopkins’ poems, in which Christianity obviously features quite heavily, was like the madness of contesting and dealing with your faith.

Jonathan: I think that’s interesting because church was very connected to your process of growing as a writer, especially in having these formative moments encountering poetry via a churchmate as opposed to via school. But at the same time, in terms of the presence of faith in your life, it was complemented by these people who are writing about the madness induced by spirituality.

David: Oh yeah, but that’s a temperament thing, right? I’ve always struggled with the question of what it means to be part of a church community. Perhaps in a bit of a C. S. Lewis-bent where you’re fully aware that you don’t really fit in. It’s just a factual thing where temperament-wise, interest-wise, you’re apart from most people in church. But at the same time, learning to be happy coexisting as part of that body takes a long while. I still struggle with it to this day.

Jonathan: That reminds me– there is a quote, I think from Christian Wiman, who said something along the lines of, “A poet is never at home anywhere”. Maybe there’s a bit of that we think of feeling that sort of disconnect from the church context, especially when there can be a bend toward a sort of conformity.

David: Maybe especially for like my, your generation. We kind of inherited the evangelical wave, at least here in Singapore from the US. That had a fairly massive cultural impact on my generation and for a lot of people, that was it, right? That was one of the breaking points. If you were going to stay, you would have to navigate these cultural structures. There were even people and waves associated with the evangelical movement like, the guy who wrote I Kissed Dating Goodbye. There are really common things that were in our church ecosystem, culturally at the time.

I felt from that early age, the moment I saw it, like man, in Jon Stewart’s language, you smell the bullshit immediately. Obviously, it’s a personal response, but for people who feel like this reeks so strongly of something problematic, where are you gonna go from there?

But just because I think it’s bullshit doesn’t mean someone else does. This is a nuance that’s really important, especially for social media today. Just because I feel it’s bullshit doesn’t mean I’m gonna say the church is bullshit immediately, right? And there are still other things that can anchor that work to be done or things to be experienced together. But that is an extra layer that needs to be navigated.

I’m very much a sceptic or atheistic by default. So that’s my starting point always, right? It’s difficult to find a home. I think a lot of this, whether you write or read, that’s part of what this stuff is for.

***

Intercession

David Wong Hsien Ming

i.m. Ken Jing

Grant him this: the lilting, blonding leaves

and a window with which to watch them.

Do not let St. Vitus visit. Let his gargles

be not on the floor but upright

and in front of a mirror. Let no child ask

why he flails like a fish on a chopping block.

Let no one question the existence of God

in his embryo becoming.

And when the storm of inflections comes.

let it come through the window

bringing the lilting, blonding leaves.

***

Jonathan: I had a similar scepticism when I was a teenager as well, but similarly, I think I’ve found things that I felt were important that church provided or faith provided, especially that feeling of being moored to something.

Do you see that as also coming through in the kinds of poetry that you were writing or seeking out? This idea that there is something redemptive that was at the heart of it, that kept you within the fold of faith?

David: I think whether it is I’m writing or seeking it out, I think something that remains from ugliness, something maybe a bit insistent without being milquetoast or trite. I think redemptive is a bit of a difficult word to use. Let’s say, if we’re just talking about me writing something or producing something, if someone else finds it redemptive, that’s fine. But I don’t think I ever start with that in mind.

I guess the spirit of it is what remains after this ugly image, what remains after this situation that, appears in the poem. Maybe sometimes we can see that as a form of beauty. I don’t think I would have said this years ago, but thinking about what I am still writing and what I’ve written in the past, I think there’s always something to be stubborn about, whether it’s a feeling, whether it’s a political social position, whether it’s an image or memory. To try to make it a bit challenging, even if we’re stubborn about the ugliness of something, I don’t think the goal is honesty only. This is a bit harder to articulate.

Maybe the better word is testimony or presence, right? Some sort of voice, some sort of ghost that is insistent and standing there and just kind of like being that pulse. Maybe you can call it a bit mythic or allegorical.

And if out of that insistent ghost comes beauty, comes goodness, that’s a very nice happy accident that I would always hope for, I just don’t know if it’s going to be redemptive in the end. But the idea is that it definitely needs to stand for some sort of idea or feeling. That’s definitely, one of the favourite poems, ee cummings’ ‘since feeling is first’. I think it’s my very first favourite poem.

Jonathan: Maybe when I used the word redemptive, I was trying to think of the poetry as a mirror to your own faith, like the idea that there’s still something redemptive about faith that has kept you with it as opposed to giving up on church altogether.

But at the same time, I guess the other idea that you’re talking about is like a remnant or almost like, if you take it more cynically like the ruins of something, what survives after a huge tragedy or something devastating.

Which is where maybe there’s a possibility of beauty, but that’s not necessarily what you’re trying to get at either. It’s just what remains, and maybe as you said, that pulse or the thing that is consistent comes back to this sort of faith or presence of some kind of faith or something.

David: Yeah, because if what remains in the ruins or what is still there is like humanity, it’s not exactly the most personal word to use. It’s not like a person that remains, right? So then in our classical sense, it kind of comes back to big questions like, where does this feeling of joy or beauty beyond an individual person, where does that come from?

It’s always a difficult question to answer because, outside of poetry for a second, if we think about real human situations, it’s not about survival anymore, right? That’s so far in the rearview mirror because either survival has been achieved or you are already doomed and facing death or execution. The human element that insists on beauty or something redemptive or some sort of presence. That’s one of the common things that is very much the root of faith or what starts our journey off to seeking faith.

Maybe I’m a poet of stunted spiritual growth because I’m quite obsessed with that phase, whereas a lot of people in church would be interested in moving beyond it. Like, let’s look at ways to do work for the kingdom. But I’m probably quite fixed in that phase of a human being’s experience of spirituality and divinity and grace.

***

***

Jonathan: Through our conversation, you kept saying the word bone – receive a bone and throw a bone – and to me, your signature poem is ‘Now I See the Sender of all Bones’. I don’t know if that’s subconscious or not. I have been really drawn to the two longer sequences in the book: one was ‘Friday’ and the other is ‘Letters to Bone’, which ‘Now I See the Sender of all Bones’ is a part of.

But of course, these are written from a very raw and personal place after the passing of your dad. Poetry comes out of the lives that we live. It is not life in a way, but what you described of getting to that thing that survives or remains after tragedy, I think, you articulated it well and it really matches what you were concerned with in For the End Comes Reaching because it’s very mournful and elegiac, and filled with grief.

You wrote this book at that moment when you were still trying to get through the wreckage of what was going on then. Given that this book was published eight years ago, how do you think about it now?

David: I’ll mention an old Grouper, Zhang Ruihe. I think something she said probably helped me to clarify or articulate that obviously, you write with quality control, you’re not trying to put random stuff out there, because God knows there’s enough stuff coming out.

But certain things are quite apart from that and maybe this book was one of them. At least for me on a surface level, a lot of the poems that emerged felt necessary. Not to say that it was easy to write, it’s just that some poems obviously came really quickly. The overall progression of the book came from a feeling of necessity or inevitability for myself. And after that, because we are making essentially a public product, it became about how what remains connects with someone else who might be reading it. That was the hope. I think to some degree, if I’m writing those poems, if the voice in the poem is speaking to someone, it’s not really speaking to my Dad, right? Because he’s not there.

That’s part of the mindset in terms of how works are meant to connect with a reader. It’s more than just, someone dying and you’re really sad about it, so you’re just gonna write about it. That pretty much leaks a bit too much privilege or presumption, right? Because everyone’s dying all the time. Whoever’s relation doesn’t just go out there and publish a 30-page manuscript on Facebook and expect people to pay for it or read it. In terms of like, the construction of the artefact, like an aesthetic, artistic work, that was my goal.

So it’s a blending of that inevitability of what the book is, but what solidified it as something that to me felt okay to release into the world was that at some point a lot of these elegiac poems were speaking to some sort of stranger. Some of the poems are speaking to a figure like my Mum or like my then girlfriend, now wife, or speaking to a friend. But there is definitely a pretty good chunk of poems that were elegiac in nature that are just speaking to a stranger.

I think that connects to some of the stuff we were talking about today, where it’s this kind of amorphous stranger, and I’m just telling you something and through this telling, I just want to create this feeling like there is something compassionate between us.

Looking back, I think a lot of times it is an emotional state. Obviously, I was writing of my own stuff, my own memories, but it’s always speaking to some random person with a great amount of compassion and joy for the fact that, oh, you exist, you are alive. Finding the joy in the existence of other people, I think that was really crucial.

***

Letters to Bone

David Wong Hsien Ming

i.m. Wong Chai Kee, 1952-2013

1. Red Tulips

All the day death

and the spring bloom of death

cells like red tulips

along his spine

visible only when the roots deepen

and he closes his eyes

2. As With All Abandoned Vehicles

As with all abandoned vehicles

the mechanic tries a long recharge

and says to hope for the best

which means a year or less,

sometimes more.

It would take hours

before his assistants come

to warn that if too much has been spent

the only thing to do might be to wait

for the batteries to die–

I found you in the morning,

pain like an ignition switch left on overnight.

In their eyes they were ready

to replace everything.

3. A Kind of Spring

You are less

and all else

must become more.

A kind of spring

where death packs itself

into a moment

so other things

grow and begin

to die. Still,

there are things

that echo back

your absence;

fast eaters and loud laughs

and fathers dancing

for their kids in shopping malls,

their wives embarassed;

Vitalis hair tonic

and runners’ back profiles;

parts of a life resurrected

and resown.

It is not that God

seeks to compensate;

shadows argue for light

well enough.

4. Pascal Returns to Lecture

The man wakes to continue working

towards death, making names for it, trying

to apprehend the thing. To pretend that death

is more than death, that humanity

is more than what is human. God

is the last name he finds

and he asks God why.

It is a question to the air

but the air has become more than air

and the man’s pretending more

than a pretense of bravery,

the way the unkissed lie about knowing how

and so kiss all the more passionately.

It is in pretending there is more

that more is found. So the man wakes

to apprehend the thing.

5. Your Father in Heaven

Would you have me say instead

that God has come as cancer?

O God, why did you come?

Why did you stay when the machine dutiful

puffed out its last breath of radiation

and warned that visiting hours were over?

Christ. Your Father in heaven

–hallowed be His name–

has he checked the clocks

in the book of names?

Tell me, son to son:

is anything divine

to a waiting mind?

So if His kingdom comes

and if His will is done:

see that it is so

in my father’s body

as it is in heaven.

Take back this day

my daily bread

and tell me, timekeeper,

teacher, old-maned

name-breaker.

tell me, just tell me,

is it today?

6. Now I see the Sender of All Bones

Now I see the sender of all bones,

love heartgrippingly woven and achingly naked

ripping through every street and wire and ventricle

that in the hush of a birthday surprise waits to be found.

I see in the subnatural buzz above pain-moistened skin

the torrent of extra-ordinance and omnilogic

that is God.

God, who lets us say to his face

there is no God. And to that face

brave is the hypocrisy of my father’s smile

brave is the sound leaking from his punctured trombone mouth

brave is the rout on this nowhere bridge his spine

brave is the cocoon of his hand holding mine

brave is the it’s okay he says when I ask is it today

brave is the parade of urine jugs the nurses have become

brave are his muscles, that like old dogs whimper and drag themselves to his call

brave are the generations of painbearers whose stories are written in piss and shit

along the toilet bowls of his ward.

So I say wreak joy to my wreck when she asks is it today:

wreak joy into the nightlights

wreak joy into his bones

wreak joy through the valley till the valley is a road

wreak joy with fenced eyes and bent breaths, make them into joy-clouds

wreak joy, my mother, my root’s river

wreak joy into today.

It is today, it is today,

it is today.

***

Jonathan: That sense that there is a presence of someone else with whom you are able to exchange and share particular pains or griefs. Maybe that is so much of why the book has resonated with me, with friends, but also through the ways that you have inverted some of what we talked about – that very plastic church language. I mean, ‘Now I See the Sender of All Bones’, lines like ‘Your Father in heaven’. ‘Would have you me say instead / that God has come as cancer? / O God, why did you come?’ Even the kind of very anaphoric lines ‘wreak joy into the night lights / wreak joy into his bones.’

David: I guess if we’re speaking in the context of The Group to like, what does it mean to be a creative who is also a Christian, I think that’s a wonderful thing that should be embraced and I don’t know if it’s embraced enough. I’m not connected enough to our Christian creative circles, but from the little I’ve been exposed to, I kind of still feel like the skin is still a bit thin. People need to seek out distinctively non-spiritual avenues of critique. As long as these people recognise that this person is trying to create some sort of document about faith, and you need that perspective, right? Again, I haven’t worked with a lot of Christian creatives, but whenever I have, that’s a constant disappointment for me. And I’m not just talking about Singapore. I’m also talking about the States and elsewhere, with classmates or peers who happen to be writers, but also Christians. And instead of taking it on as this wonderful opportunity, they felt very poorly. Like hey, why is it that no one’s giving it a chance when I write all these praise verses about God? You’ve got to dig into the reason why people are not responding well, right? It’s not about successful evangelism. It’s about successful connection, which is of course a precursor to sharing things. You’re never going to connect in that way and that’s a bit of a pet peeve of mine.

Jonathan: And then of course when we talk about the inverse and you brought this book and your work back to church. Was there then a reverse kind of feeling? Not that, oh why is it connecting with people, but more why is it not more explicitly like a praise verse? I also don’t know how many people in your church, actually read the book.

David: Yeah, I don’t exactly expect that of my faith community. We’re not super steeped in the tradition of the arts. I guess I see my creative journey, like, it’s there for random people to find if they want to. But the fun part is that some Christians might get a bit confused about my poetry. I think it’s maybe a reflection of the nature and current cultural state churches in Singapore.

In church, there’s a certain conceptual template of what cultural stuff looks like. I don’t mean to come off as dismissive, but in the past when we were young, it was like okay, we will sing the Hillsong stuff, and then we’ll go into a praise segment onstage and now it’s evolved into like we’ll have a dance with streamers or whatever. I’m not denying that’s evolution. But the problem is that that’s evolution along templated lines. I think it’s a genuine struggle. It’s very difficult for the church management or people within church to figure out how to navigate culture and make creative things distinctly our own. Because there’s always this structural need to say that this is like, stamp chop Christian in nature. I think whenever we do that, the battle is often already lost.

That’s the privilege I have as someone who doesn’t run a church, right? If you’re pastoral staff, you’ve got to think about these things. I think that’s why it’s the artist’s job to do these things because it’s sure as hell not the pastor’s job. As an artist, you live in the liminal spaces. If you’re an outsider, you’re an outsider, and you just do the work and form that invisible thing for all the random strange people to go see if they need to receive that kind of thing.

Even though I don’t always do a good job, it’s still important to me to be part of the church for whatever little it’s worth if somebody is watching out there to know that church is still more than one kind of person, one kind of activity. You have a place here, right?

***

Circles

David Wong Hsien Ming

“The image of the progress to infinity is the straight line…bent back into itself, this image becomes the circle, the line which has reached itself, which is closed and wholly present, without beginning and end.”

– Hegel’s Science of Logic (1969), p149.

your end was a beginning of sorts.

I returned to you dancing in the middle of the shopping mall,

me staring at the big Christmas tree, pretending

not to be your son, mom pretending not to be your wife.

I should have watched you dance.

Now, two feet from your deadness,

I make SoMyeong hold the nicest funeral flower

and take a picture, one that you appear in

but are not a part of.

The time it took your body to break

was time enough for all of us to form a circle

and from your coffin you facilitate

your last team-building exercise.

Eventually the circle breaks. No one knows how or when it breaks.

It could’ve been a cough or a cry, your godson’s smoke break

amidst the brick memorials of those deader than you,

or a mispronounced word during the closing prayer–

no one knows, but the circle

breaks, as all circles must, into new circles

that are themselves rejoinders into something larger that always

or never was, and we know this. We know this.

There is no samsara if we know this.

I kept telling you Hegel was right

but I was wrong– we are not infinite; our absences are.

Your absence is, and we encircle it. And because we encircle it

you are no longer part of the circle.

You are beyond that now, while here I am going back

on this gibberish about how Hegel was wrong

when yesterday I said he was right, and tomorrow

I might go back on today, since

***

Jonathan: I feel like you are now engaged in your own different kind of creative work through teaching. I’m sure that also draws a lot of your mental, emotional, and intellectual energy on a regular basis, but I was curious to know if you’ve had a sense of how your writing has informed your teaching.

David: Definitely. I would say if I’m trying to throw myself a bone, I think it definitely prepared me for some of the cultural work that can happen in a profession like teaching. We do have Christian students who very often cannot believe that I’m a Christian. Like are you just saying that? Are you trying to troll us? But like no, guys, heart on sleeve, I’m serious. I believe the same thing you believe, but the way you practice is probably quite radically different.

And I’m not trying to tell you that you’re being the wrong kind of Christian. The point is not to make them like me, right? The point is to show there are all these different ways in which joy, beauty, or whichever faith-adjacent word you want to use operates, right?

That definitely prepared me.

***

Eschatology, or the loss of a job

David Wong Hsien Ming

Look at the wind, called to tell

of the last word, its breadth gathered

into a tidal weightlessness upon the execution block

—a washed cheek upon its lover’s palm.

There is grief on the skin, which knows

there is no wind in heaven,

that destination’s temporary hands

cannot carry the weight of the journey.

Call loss the price of grace,

if that makes things easier

—what does the skin know, anyway?

Only the smearing of atom upon atom.

Only that being is the only broken thing

that breaks again.

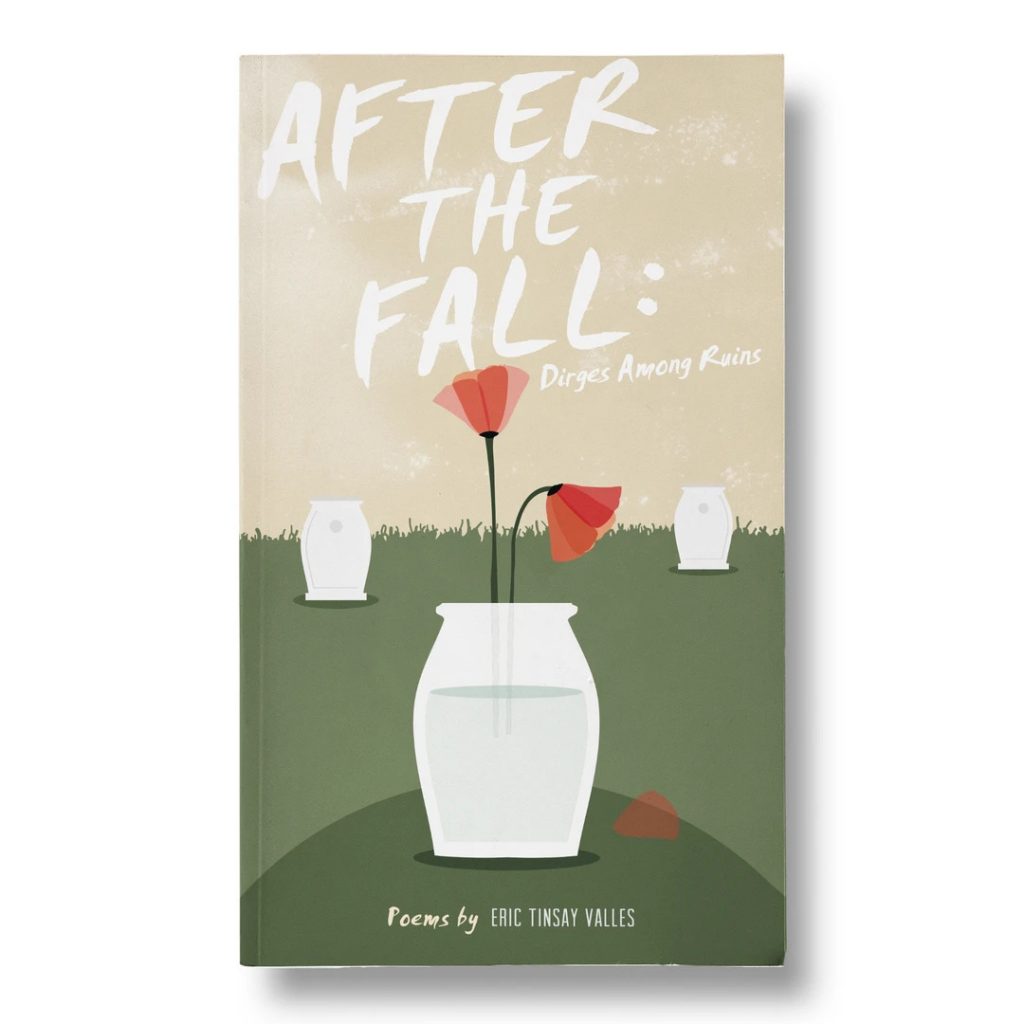

The first four poems featured are from David’s collection For The End Comes Reaching (2015). The last poem was first published in A Given Grace: An Anthology of Christian Poems (2021), edited by Eric Tinsay Valles and Desmond F. X. Kon Zhicheng-Mingdé.

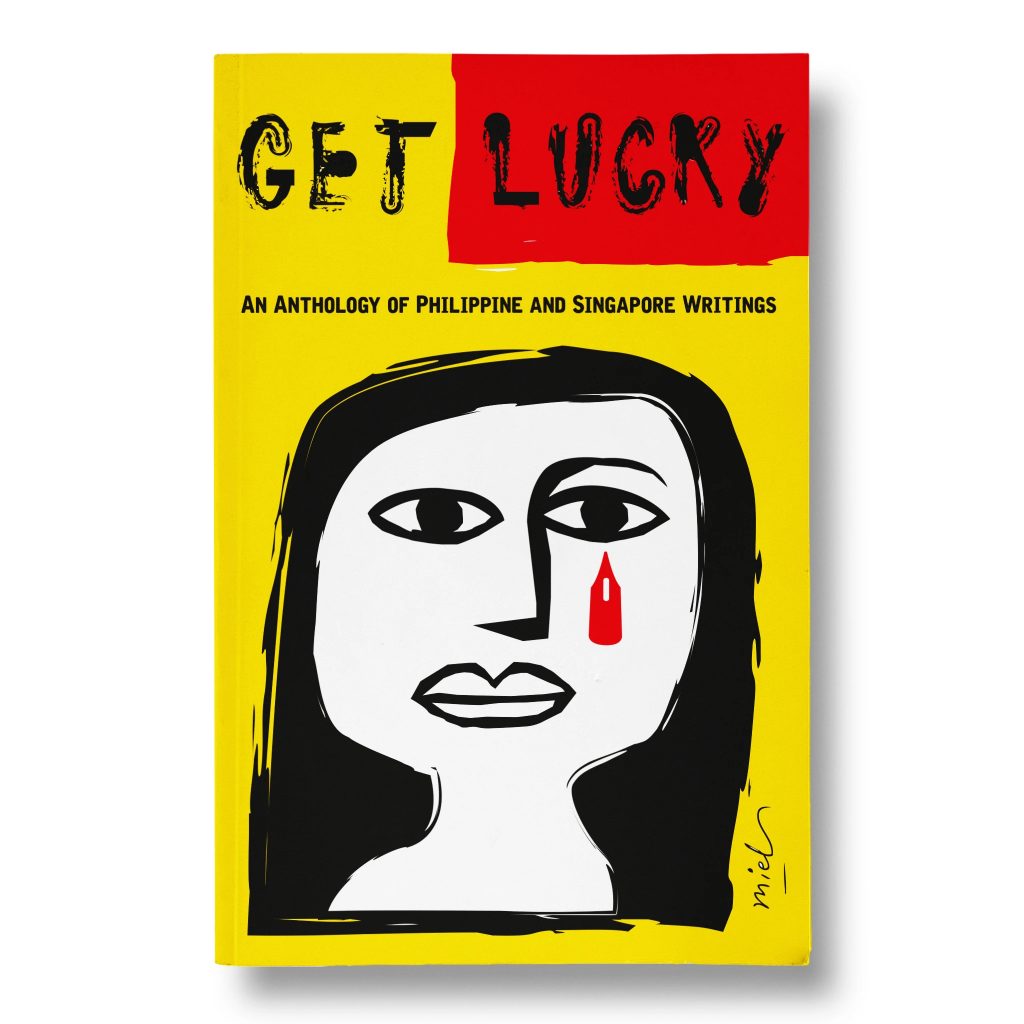

More of David’s poems can be found in Food Republic: A Singapore Literary Banquet (2020), Quiet Loving, Ravaging Search — 20 Years of Quarterly Literary Review Singapore (2021), and A Luxury: Omnibus edition (2021).

Cover image: David performing his poetry at Sing Lit Body Slam: 2 Much 2 Soon, a combined poetry slam and pro-wrestling event, at Aliwal Arts Centre, Singapore, in 2019.

Website: https://davidwonghsienming.wordpress.com/