Mike Wong (b. 1967) is a multi-media artist who works across the platforms of painting, video, theatre, and installations. Having received training in Western and Chinese art and studied engineering in his academic years, while still being mostly self-taught as an artist, Mike has a unique perspective and approach towards his art-making. He lives and works in Singapore. His art has been featured in exhibitions in Singapore, New York, and Chicago.

Jonathan Chan interviews Mike about his thoughts on making art, the place of faith in his creative process, and his position as an artist working in and outside of the church.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

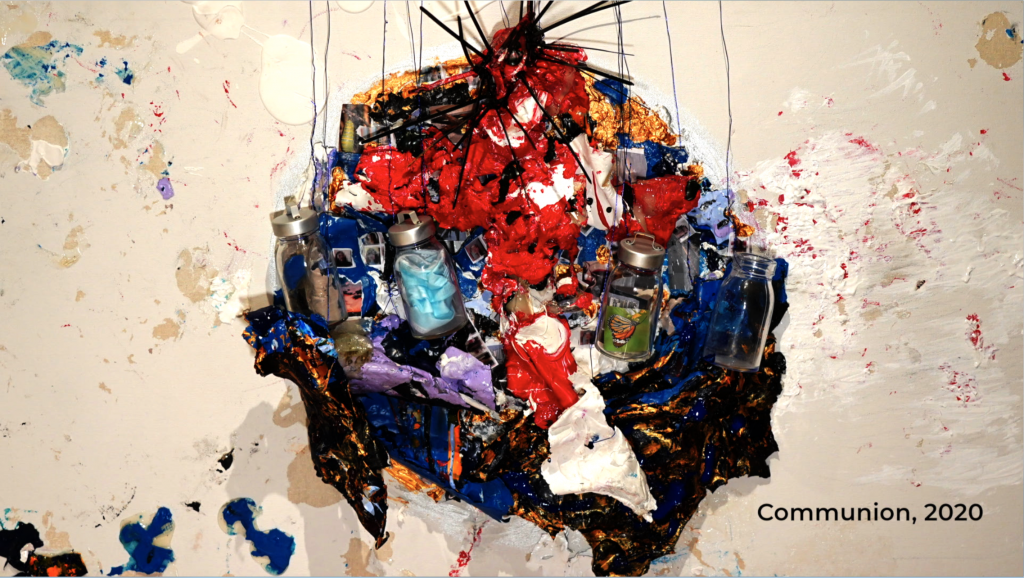

Jonathan: I thought we could start by speaking about ‘Communion’, the piece that you prepared for Easter last year. I thought it was powerful that you took a piece called ‘Voidness’, took it apart, and you put together over it this visual expression of the coming together of the body of Christ beneath the bleeding crown of thorns. It presented a sense of coming from nothingness into the substance of the church itself.

Why did you choose to work over that piece in particular and was it something your church commissioned you to do?

Mike: When the pastor of my church approached me, that was when the entire church was given the notice that they were not allowed to meet anymore when Singapore was under lockdown. He asked me, “Do you have anything with which you are able to encourage the congregation through art?” He’d given me a blank cheque, and I like blank cheques because when I deal with art, I want to sense on my own where I should head to.

At the beginning of the year 2000, I began to experiment with bright colours in my paintings – using the paint in its original form, its original hues, and not mixing the colour so much. I would use the technique of applying and taking away, so it was always a continuous process of letting it dry or half-dry before I would just tear it off. That is my practice with the abstract paintings I’ve done and part of what I was doing with my solo exhibition in Chicago in 2013.

The reason why I chose this particular piece is that when I was painting ‘Voidness’, I’d had enough of colours that shout because that was how I was seeing the world. To draw attention, whether it was in the commercial world, the religious world, everybody was shouting! So that’s why my paintings were loud, bright, and colourful. People may think they’re cheerful but behind that brightness, I was criticising the unbearable loudness of it.

And then COVID-19 came. I felt that it was like God giving a pause button. You couldn’t speed anymore. Nobody could. And even churches, with what was supposed to be a year of reaching out to the lost, couldn’t! So I didn’t see 2020 as dark and gloomy in every way. Of course, there were moments where it was depressing, but that is only because of our indulgence in this speeding world… our indulgence in always trying to brighten everything, you know?

So I decided to do a very contemplative piece that says: what better way to tear down the brightness, the emptiness of the past, pause for a moment and, focus on what really matters: what is the anchor of our faith? I think that was the message: that we are all having communion together not just of bread and wine, but also of His death and His resurrection on Easter Sunday.

Jonathan: I’d be interested to hear how your pastor responded to it, and your fellow church members as well. Would you say there’s a place that the arts occupy within the consciousness of your church and how it does ministry?

Mike: For people who are not so exposed to art in general, they actually had no clue what was going on, though they did feel that the metaphor of tearing the old painting down was a bit shocking. They were like, why is this guy tearing down all the different paints? They were more curious about the material that I was using, that it could be torn down and be taken apart. I was glad that they were curious about it and I was hoping that they would be. I was also hoping that there would be negative remarks, but they were all very courteous and nice lah.

The relationship between art and church is always like that. In Singapore, particularly, I find that people are not so exposed to the art scene or to art forms, so in terms of paintings, I think they would think that paintings are all the same. It has to present something, it has to say something, and it has to be about something.

Jonathan: Would you say then that part of that perception comes from the sense that art should only depict “serious things” or matters of social concern?

Mike: Yes. I think for all these years I’ve been working with the church, whether it’s been in paintings, theatre, or videos, if art is not useful, then it’s not needed.

That is what I have always tried to educate the church about: that art is not something you’re supposed to quickly bend to your needs. Rather, it is in its most un-useful way that it is useful. Do you know what I mean? Why does God want to make the skies of the evenings and mornings so different every day? He could have just prescribed one shade or hue consistently throughout, yet every day is different. There is no particular need for them to be different. So in a way, I think this is how I see how the church and other institutions. They always look at art as something that has to be useful.

When I do theatre in church, often they are looking from the angle of a sermon. I always have to tell them that sometimes what I’m doing on stage is experimental, and may not even be theologically correct. However, I’m quite fortunate because the pastors do allow me to experiment to a certain degree. After a while, they’d say, “Can you stop experimenting?” Because most normal folks when they come to church they don’t want to think too much. They just want to be fed. Then I’d say, “I’m not the person who’s supposed to do this because it is not my inclination to do that.”

So that’s my relationship with the church. Historically, a lot of Christians have had that struggle with the church, like in the time of Michelangelo with the struggles he had with the Pope. I guess all Christians who are artists in their churches will have that kind of struggle as well. Art is like a bulldozer that tears down walls, or at least a means of opening a window or a door. It’s a catalyst – such that you might be inspired to explore, find the truth for yourself, and own that truth. It is my belief that that is the duty and responsibility of an artist, especially for a Christian artist.

Jonathan: I guess that’s one of the tensions we always have to navigate – that feeling of the accessibility of what you create. I think it’s interesting how there is a spectrum of work you’ve presented for the edification of the church – some experimental and some more straightforward, parable-like work as well.

This is a good place for us to transition to talking about your career because just as there are struggles that accompany being an artist in the church, I’m sure there must have also been difficulties being a Christian in the art world. In particular, I was interested in talking about your exhibition The Dramatics of Living (2013).

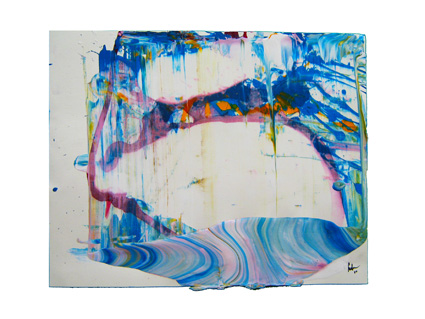

I read what you wrote about wanting to be a facilitator of how paint moves on the canvas and I thought that came through with the pieces for that exhibition, including one I like called ‘Quiet Foam’. To me, the paint stacked on itself in a way that almost looked like cake icing. I was curious about the process of bringing that exhibition to life and the interaction that process had with your faith.

Mike: First of all, I’m not involved full-time in artmaking. I was an engineer and until I really had no more energy or inspiration left to be in engineering, I was telling my wife, “I really want to be a full-time artist! I just want to paint for the rest of my life”. And my wife was like, “Are you sure we are not going to be hungry?” (laughs) I was thinking, okay, maybe I will paint when I have time and give myself work that will be able to bring in the bread and the butter. So I started Stampede Pictures, a video production company doing wedding videos, but soon went into corporate videos and commercials. That’s how God has led me.

The Dramatics of Living was during that period of my life when I felt I was doing so much commercial work where everybody wanted to tell the world, “Hey look at me! Look how fantastic I am!” I love what I do in video and film production, but I was getting fed up with all the overly dramatic promotional videos I was making. For me to create all those artworks afterwards – that was my reflection lah. That was my anger: that it was overdramatic all the time in the commercial world. And everyone artistic has to be angry about certain things so that the work has that content that people will be able to resonate with.

That’s why I was trying to bend the paint and the medium- it’s acrylic paint actually. It’s plastic paint. And I was trying to bend it in a certain way that was hard to bend as an expression of how my world was in day-to-day living. It was almost like you had to bend every aspect of yourself to suit what the world was wanting from you. That’s how the exhibition was conceptualised.

The American art scene surprised me in a big way because it’s very different from Singapore. They were much more receptive towards the abstract and their curiosity was like… Wow. I created an installation in the middle of the painting exhibition– it’s literally a cardboard box, and in the box, I put a television inside with a video of me drowning. When you go in and have no more space to look around, you get the feeling that water is filling up and you are drowning with me.

That piece of work created a lot of interactions- a lot of people were crawling into it, especially kids who liked to crawl into spaces like that. That piece, somehow, created conversations that I really loved. I’d have people walk up to me and tell me their whole life stories. It was like… “Shall I tell you my dark secrets now?” Do you know what I mean? And that’s what was really delightful for me at that time in Chicago. Different people would just come up to me and tell me how their lives were wrecked by alcoholism, drugs, or whatever else. I was like, “Wow, you’re telling me this?” Would people tell me that in Singapore? No, they wouldn’t.

Somehow that changed the way I staged that later on in Singapore, as I felt that Singaporeans would not walk up and tell me about their lives like that. So I created a box where they were able to put in notes or items that they wished for me to destroy for them. That’s how I felt Singaporeans or Asians could communicate- by leaving things behind. There were people who would write about what they went through in their lives and put it inside the box. Some of them wrote in Japanese. I could not even understand what they were writing, but I created a ritual to burn and erase them so that it would symbolise that part of their lives could be released.

Jonathan: That’s almost very sacramental, like a confession box in the Catholic tradition, that realisation that comes with articulating what you’re struggling with. I suppose it must have been that feeling of drowning that must have drawn something out of a lot of people – that claustrophobia that made them reflect on the conditions that made them feel like they were drowning in their own lives.

Mike: That’s right.

Jonathan: It’s like you said: the role of the artist is different from that of a preacher in the articulation of truths or the beauty embodied in those truths. I was looking at some of the other pieces that you did in 2013, especially ‘Jubilation’ and ‘Arise’. Those, to me, had a very intuitively Christian feel to them, maybe because these senses of arising or jubilee are very biblical ideas. At the same time, while I was thinking about them – the drip painting, the tape – those kinds of mixed media approaches reminded me of the works of Jackson Pollock, Cy Twombly, even some of Anthony Poon’s paintings.

Given that you have had these experiences of exhibiting your art in different contexts, do you ever feel this tug in considering how your pieces are going to be received by different audiences?

Mike: When I’m creating I don’t think about the audience because I know the minute I think about the audience, the work is gone. It does not come from me anymore. It’s a reflection of the audience. I do hope more people will like my paintings and want to purchase them for their collections, but I know that the minute I’m tempted to paint what an audience would love to see, the originality of how I conceive it will be gone. There have been times where I would have to destroy the work because one day later I’d go back and look at it and say, nah. This is not me at all. I don’t think I can live with it to show such work no matter how beautiful it is to me.

Most of the time I just want my pieces to communicate what I intend for them to communicate. Most of my work is fast, quick, and spontaneous. Sometimes I do not know what colour I’ll apply to it. That is very much in the moment, what people would say is action painting, but I would purposefully destroy that action or bend that action to another way… so it would not look as if it is an action. It’s conflicting when I’m in the process.

But I love painting because every time I do a painting, I can feel that there is a spiritual sense to it… That I am in touch with someone or something. Being drawn into it – it’s out of this world. Your presence is no longer measured by time or limited by three-dimensional space. It’s like your whole being is having an out-of-body experience. I love painting because the more I get into it, the more I get that communication with God, I think. So it is a form of worship to me as well.

Jonathan: That’s very powerful, especially given that painting was part of your life even before you knew the Christian God. You mentioned learning different techniques growing up – Chinese painting, European and American painting styles – that have all now converged in your practice and been refracted through the lens of faith.

Mike: Yup. For my works of art, it’s always about my struggle with and understanding of the Christian faith. Struggle because I believe the Christian faith has to be struggled with. If there is no struggle with that faith, I don’t think it’s faith anymore. It’s really not easy to believe in something that you cannot see or cannot touch. When you picture Christ, every one of us has a different image of Him. You know, we may draw inspiration from the Romans, from the medieval paintings, or the modern paintings, or whatever that has struck us – whether He is yellow, black, or white.

But I think, in a lot of senses, God has to be experienced in the spiritual form, and the medium that gets to it, whether it’s text-based, or paint-based, or sound-based, I think He has a way to reach out to us through them. You look at how He painted the sky for everyone to be able to see His greatness – I think that is enough. It doesn’t need a lot of explanation.

Jonathan: Beautiful. And unfortunately not always the kind of thing that can be communicated in a video or a skit to a congregation.

Mike: (laughs) Yes, it’s not something we’re always able to do. But I’m really into using technology and fusing it with art so that I’m able to communicate this Jesus whom we so love. There was one theatre piece I did about six years ago, where we converted the two-storey church car park into a dramatic space and called it the ‘Final Hours’, inspired by the Stations of the Cross. That work was about the final hours of Jesus, from the time He entered Jerusalem on Palm Sunday to the Resurrection and used technology and stage play to let the audience walk through the stations themselves.

There was one particular station inside a black box where audience members would be ushered in by Roman soldiers. The wind would blow around them, dust would blow upwards, and they would not know what was happening. Once they stood behind the luminous line, the lights would come up and they would actually be standing at the bottom of the Cross. Jesus would look down at them and utter, “Father forgive them for they know not what they do” until it was finished. A lot of them could not hold back their tears.

The other thing was that I had an infrared camera that would capture the faces of the audience, and I’d project them onto the ceiling. They would literally be seeing themselves looking at Jesus. And a lot of them just looked away – they could not stare at this screen of themselves looking at Jesus, they could not stare into the face of Christ. But they had to decide who this Jesus is.

Jonathan: As a last question, I wanted to quote something that you’ve written to get a sense of your thinking. You wrote:

“Spontaneity is spiritual. It is mysterious, unpredictable and always explorative and experimental. Can spontaneous notion be engineered. Spontaneity is almost exclusive to humans. I may be wrong but no all-knowing and higher beings can have this experience.”

I was just wondering what you meant by that and what it makes you think of now.

Mike: The question I still have and the mystery I’m still having is whether God can be spontaneous. You know, I asked my pastor about it. I asked him, “Can God be spontaneous? Is God capable of being spontaneous?” And he said he did not want to attempt to answer it and said, “Why don’t you explore?”

So I’ve been asking people, what do you think? Do you think God is capable of being spontaneous or is it something that He is not able to do? In other words, I have an advantage over God! I can be spontaneous, while God can’t! (laughs)

The more that I dig into it, the more I observe, from my own human understanding as the years go by, I think He can and He does it much more beautifully than we do, but not in a way that we really understand. So, I do not really know how, but I have this sense that He can, that there is a spiritual aspect to the spontaneity that is not bound by time and space. So what do you think? Do you think God can perform spontaneous decisions, from your understanding?

Jonathan: Part of me thinks about the foreknowledge of God, and how what may appear as spontaneous to us might not actually be. But at the same time I also think about how, as you said, spontaneity is something that is very human, because we act responsively to constantly changing variables. I think of how God became man and so became Himself subject to that uncertainty, and how the Holy Spirit, in His interactions with us, operates in and around our fickleness. So my inkling is that God can be spontaneous, even if not necessarily in the way we might think.

Mike: (laughs) Well, it’s a mystery, but it’s something that I think is fun to think about, you know? Art is like that, where sometimes you have to explore certain things and not be too afraid to explore them because this is the span of life where I believe we can explore within certain parameters that God has given us.

Jonathan: That’s a great place for us to end. Thank you so much, Mike.

Mike: Thank you very much.