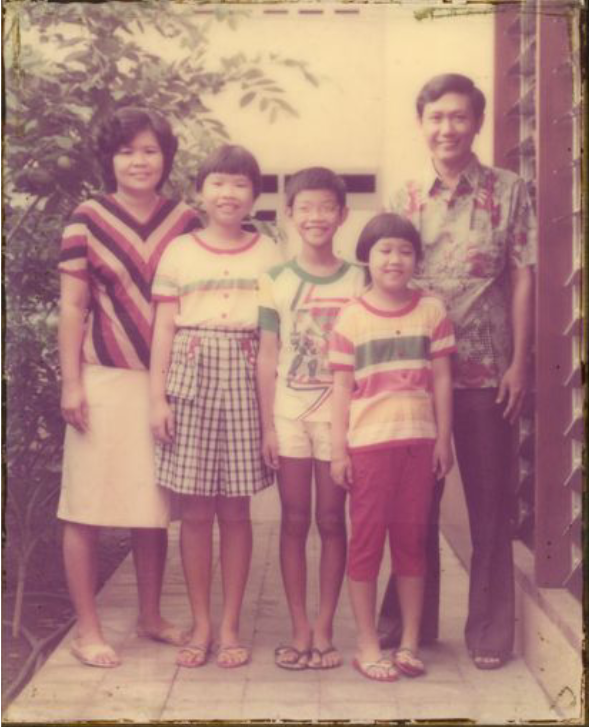

Boedi Widjaja (b. 1975) was born in Solo City, Indonesia, and lives and works in Singapore. Trained as an architect, he spent his young adulthood in graphic design, and turned to art only in his thirties. Widjaja’s childhood urban migration due to ethnic tensions, living apart from parents and rotating amongst stranger-families, informs his investigation into concerns regarding diaspora, hybridity, travel and isolation, often through an oblique, autobiographical gaze. The artistic outcomes are processual and conceptually-charged, ranging from drawings to installations and live art. His recent accolades include being shortlisted in the Sovereign Asian Art Prize (2015) and named one of eleven ArtReview Asia FutureGreats (2014). He recently completed a research residency that was supported by the National Arts Council Singapore at DRAWInternational, Caylus, France.

Boedi Widjaja (b. 1975) was born in Solo City, Indonesia, and lives and works in Singapore. Trained as an architect, he spent his young adulthood in graphic design, and turned to art only in his thirties. Widjaja’s childhood urban migration due to ethnic tensions, living apart from parents and rotating amongst stranger-families, informs his investigation into concerns regarding diaspora, hybridity, travel and isolation, often through an oblique, autobiographical gaze. The artistic outcomes are processual and conceptually-charged, ranging from drawings to installations and live art. His recent accolades include being shortlisted in the Sovereign Asian Art Prize (2015) and named one of eleven ArtReview Asia FutureGreats (2014). He recently completed a research residency that was supported by the National Arts Council Singapore at DRAWInternational, Caylus, France.

Dawn Fung interviews Boedi on issues of art making, displacement and faith.

Dawn : I am going to come clean. The more I interact with your work, the more painful it feels. It doesn’t seem like that in the beginning though, which is more interesting for me. Because your work is presented abstractly, it is a good defensive layer for me as a viewer to comprehend it in my own time.

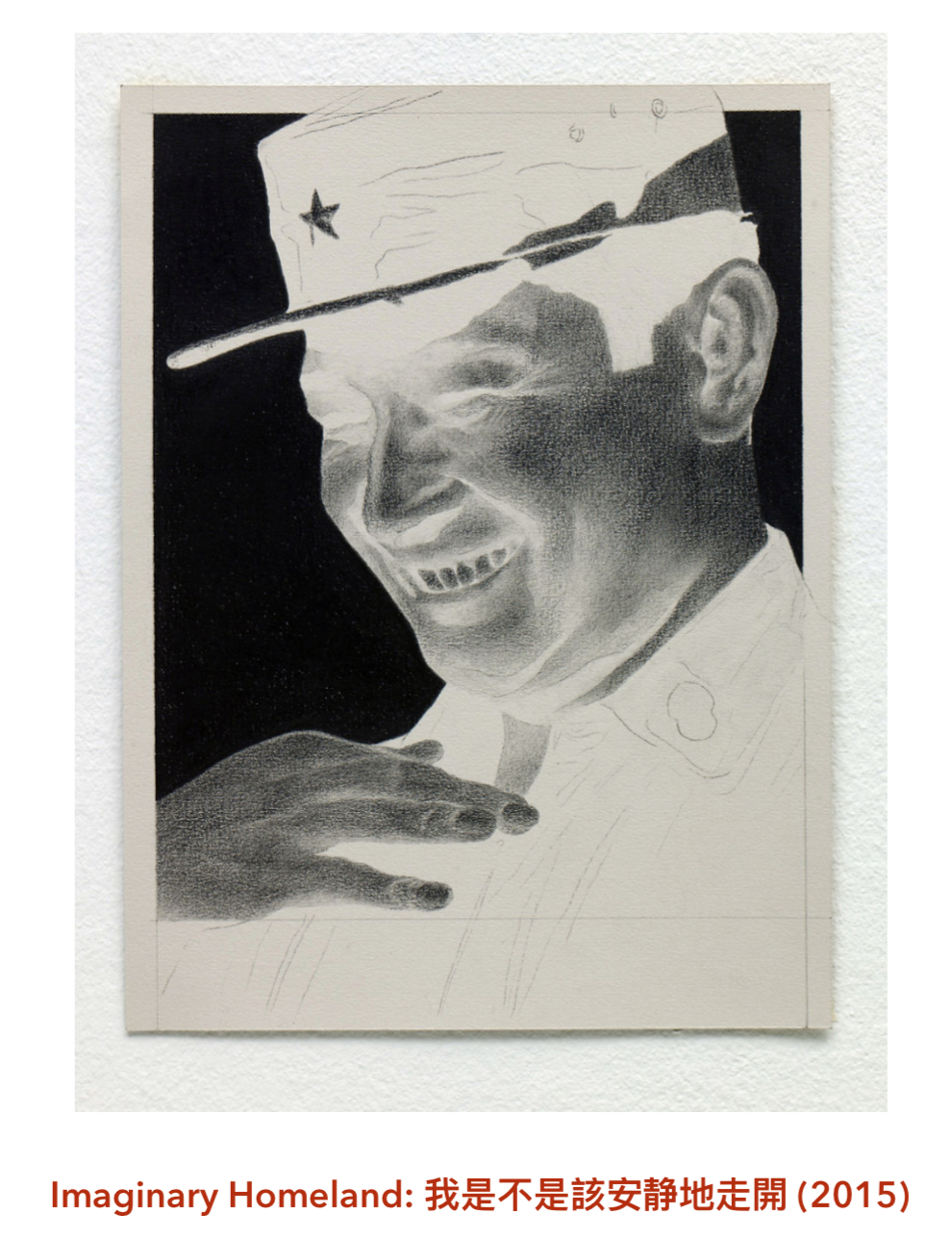

For example, Imaginary Homeland: 我是不是該安靜地走開 (2015). These are reconstructed images of political figures. Political figures in the context of Indonesian history are not romantic, humorous nor delicate. They are terrifying because they wielded power that resulted in, or from, displacement, pain and irreconcilable conflict. But you’ve managed to soften what they represent at first glance with pencil drawings accompanied by titles which are lyrics from Aaron Kwok’s pop song.

Boedi : In Imaginary Homeland I framed my work from personal perspectives, feelings, childhood experiences and memories. The work process inevitably touches on politics, especially about circumstances in which my parents sent us here. I’m not a political artist – I don’t make work that way – but my personal story is so entangled in political issues that my body of work often seems to have ended unresolvedly, which brings back to your perceptive point about how my work is painful. You’re the second person to tell me that. The first is an artist friend who said,”Boedi will stop making art when he’s happy!”

But my art making is also not set out to consciously resolve any pain. I just like to dig deep, and in that process I find things that I was previously unaware of. I think in my commitment to be authentic as an artist, I have to be personal. And how human it is! Singapore seems busy and prosperous on the surface, but it means we overlook things lodged deep within us. I am interested to find these things, and relate them through my work.

Dawn : I read the artists’ book, INSITU Fort Canning Hill (2011), a project that you co-founded. I found recurring motifs about displacement and excavations. You know, most people dig to do something afterwards, like build a foundation or plant. What I am seeing in your work is how after you dig, you’re telling the audience, “There it is!”

Boedi: I think you are right. I always remember the Indonesian soil, especially the smell of Solo. I didn’t grow up in the padi fields but I remember its smell intensely because our family took walks near Bengawan Solo River in the mornings.

I remember also the smell of urban Singapore which I didn’t like. It was the smell of an unfamiliar city. One of the smells I couldn’t forget was the new mattress that my first guardian bought for us. It was the first bed I didn’t like. It smelt synthetic. Of course I was missing home. And I still remember it.

Dawn: The Jewish Diaspora and Palestinian waja come to mind especially because you passed me Michael Morpurgo’s “The Kites Are Flying” for me to read. In these two groups are epitomised one of the insufferable problems of displacement: It will not go away.

Boedi: Exactly, but you learn to deal with it over the years. Until I got my Singapore citizenship, I belonged neither to Indonesia nor Singapore. When I did get my pink IC card, I was expecting to feel much better. I was officially a person with a home in a country I belong to. But the displaced feelings didn’t quite go away. They amplified after I got my pink IC, because I now felt like a Singaporean who did not feel Singaporean.

I realised to deal with it required a renewal of mind. How that looked like was to extend my past memories to the present, because I have been living with truncated, calcified information. This triggered my Path. series, where I revisit my childhood memories of being a foreigner in Singapore.

The first was titled Path.1, The White City (2012). When I first came here, I didn’t know about the local culture nor did I speak much English and Chinese. Even the builtscape was different to the one I was used to at Solo. I extracted that experience to be a pure white room, a spatial expression of a void. The void was to be transformed by using collective bodily movements to fill up the gallery space with man made marks. It was a personalisation of a void by the artist and his community. I can only grasp ‘social space’ theoretically and not viscerally (as I never lived through it) hence the need for visceral strategies and outcomes in the work Path. 1, in order to extend my memories. When I think about that memory now, it is no longer truncated but it has been extended to the present as expressed by that work. The marks evidenced that change.

Dawn: The Path. series are framed around autobiographical accounts of your relationship with your biological father.

Boedi: He was the central mover in my story at that time; the one who physically brought us here to Singapore, the person we said goodbye to after each visit, the person most involved in our education, not our mother. (For a lot of people it is the other way.)

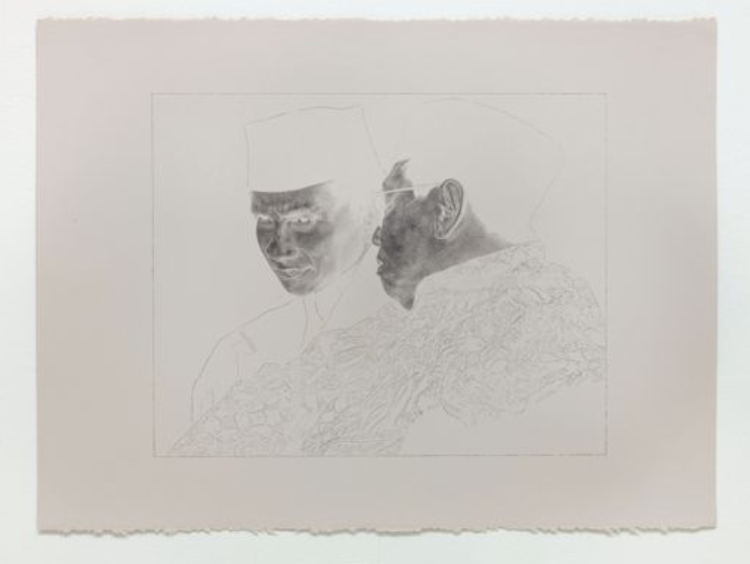

Dawn: It is interesting to note that the political figures in your work are national fathers. They moved people and things with their policies. I suppose Imaginary Homeland is sensitive because you are first, a displaced person and in particular, a Chinese from Indonesia.

Boedi: I know the issue is sensitive. I thought a lot when creating the peci installation because of the connection with Indonesian identity. If I may illustrate it like this via a dialogue I had with a curator :

“This peci is a symbol of Indonesian identity, hence, I am using it.”

“These are symbols of your exclusion.”

“I think so. It is a symbol of an identity I was supposed to have.”

Whenever I start thinking of my Indonesian heritage, the political context is the first I negotiate with, given how vivid and visceral the issue means to me. I had to leave home, my parents, because of ethnic tension, because of politics. I left Indonesia during the Suharto period in ’84. The tensions flared up in the 1998 violence.

Recently I read an article on Facebook “That number on the yellow University-of-Indonesia jacket” by Sioe Yao Kan, translated by Lina Sidarto. What struck me was the incredible persecution, and fear of being a Chinese in that time. Sioe Yao Kan continued to wear his yellow jacket – a symbol of pro-Suharto support – to protect himself.

People on the ground in Indonesia are empathetic to this issue. Unfortunately, politicking in the bureaucracy has brought about so much harm because of (their) power play as seen in the use of political figures in Imaginary Homeland.

Dawn: Since the affectation to you is so great, is research into displaced people groups important?

Boedi: I do like to read but I realise I cannot grapple with the issues of the “social”. I feel inadequate to speak for everyone; I never felt like I belonged to any people group, therefore, I never lived through the concept of society. This concept has been removed from me, so how I appreciate society or “social” space, is often from a distance.

When I make art, this is not the distance that I am satisfied with. Whatever I work on has to be something I connect to. It has to be something I live and experience. I think this is what the artist can contribute. There is no end to research but nothing is more weighty than ideas that have touched you or marked you. That’s the point of digging.

Dawn: As artists, we make things but we don’t go all out to explain why we do it. To go by authentic impulses is genuine because we don’t impose on our audiences; we merely express what is within us.

Boedi: That is very important to me, to make works that are somewhat structured but open ended. I always liken my works to diagrams. They relate ideas but leave you spaces to fill in the information. I want to share that space with people.

Someone once said of my work that it presents itself as naked. I like that. In that kind of space, we are vulnerable, hence, able to seek solace in one another. It is an elemental sensibility which brings about the unknown. The unknown is like a huge presence that I cannot penetrate.

I find this quality in my work. When stripped of all ornamentation, a ground that has been dug and now lies exposed, is beautiful to behold. I can see it for what it is really is, be surrounded by it, smell it. I don’t know the ground better except what my senses afford me, but I become aware of how unknowable the ground really is. I find this unknown, unknowable presence comforting.

The Aaron Kwok thing (mentioned at the beginning of the interview).

Since Chinese schools were closed, and we weren’t allowed to celebrate Chinese New Year, many aspects of Chinese culture were difficult to get to, except Chinese pop culture. See, the films and music were illegal but entertainment was a much needed escape. Piracy was rampant so you could buy from shops discreetly. I watched Wu Xia movies, listened to Fei Yu Qing and whatever was offered.

In Singapore in my teens, I continued to digest Chinese pop culture. In that time, mando-pop in the 90s was noted for a certain genre of heartbreak love songs from the biggest singers known as the Four Heavenly Kings, which is quite funny. Aaron Kwok was one of them.

The Aaron Kwok lines are placed alongside the drawings as a reminder of my heritage. It helps me to laugh at myself because I can get too serious. But my wife Audrey said there was something quite sad about that too. I guess here is another way of explaining the use of those Mandopop lines: A child feels sorrow differently from an adult. The sorrow is deep but the child doesn’t know how to treat it.

Dawn: Let’s talk about materials you use in your work. You work with austerity really well.

Boedi: One artist I know compared paintings to flesh, and the drawings beneath that, bones. I found that interesting. I suppose my background in architecture contributes to a natural tendency to abstract, formalise, spatialise, and to conceptualise a form. The kind of architectural principles that my generation was exposed to were principles post-Le Corbusier. Modernist architecture advocated the expression of the bones. This is something I will be exploring at an October exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore in 2016. In my architectural education, drawing was taught as an important critical process in the design of a building.

In my choice of materials, I find things at their barest most elegant. I also attribute this to my exposure to Javanese aesthetics. You will find a simple and direct relationships with materials. An example would be quintessential Javanese architecture, made of a stone foundation with a hole carved into that piece of stone and columns made of wood. The wood columns are simply inserted into the holes like dowels. It makes use of very simple, uncomplicated joints. This sensibility is also found in ancient Chinese architecture which did not use nails but were crafted so precisely that timber pieces were slotted into each other like a lattice under the roofs. So the heavier the idea is, the lighter the material expression.

We can use cooking as an example: If the fresh produce is so good, why intervene too much? The skills to present the quality of produce to its maximum effect, is how I choose and present my materials in my work, be it stone marking or unfinished paper drawings. Rich ideas should be lightly dressed.

Dawn: As a Christian and artist, I find God to be a source of rich material, even in the working out of our faith (see Phil 2:12-13).

Boedi: In my mind, God works through me as a new creation (see 2 Corinthians 5:17). I know there must be a purpose for everything I do. At this moment it’s still not very clear to me. What has been clear has been his love, grace and personal attention to the details of my life, which is shown through his attention to the details of my work. I make decisions in my art work without fully comprehending why I did certain things, only to discover later the richness behind those gestures.

Dawn: Can I have one example?

Boedi: Discovering new things through my old art works is an example. When people ask specific questions about my works, ideas would surface the moment I start talking about them. I attribute it to God’s presence because these ideas could not have been made by me.

I know people attribute a lot of good ideas to the functioning subconscious but I find it doubtful. The Bible says that the heart of man is deceitful (see Jeremiah 17:9) and I find that to be true of my life. I know from observing my own life, there has not much good to dig out except fear, self-condemnation and shame – wrong things I learnt as a child. These affected my decisions, which had been to compensate for this lack of self-worth, measured through the lens of worldly success.

Good, bright ideas come from somewhere else other than me. A lot of times when I think about new work, I don’t experience a linear process of making like A-B-C. There would be moments of understanding. I would also see visuals in my mind. Where do these materials come from, the visuals and keywords, as well as the connections that come forth?

On the piece I did for Beauty World Station, Asemic Lines (2012-2015):

At the point of time, we had just finished In INSITU Fort Canning Hill (2011) and were rethinking my art career. Then Audrey came across the competition brief online put up by LTA. Each station had a theme and a curator. What drew me most was Beauty World station because its theme was related to multi-culturalism. But I threw away the competition brief into the bin. I thought it wasn’t for me.

But two evenings before the submission day, on our way home, I made a connection between multi-culturalism and Asemic writing. I told Audrey, I may have an idea. We spent one day to prepare a presentation board. I had the inspiration to overlap the different textual forms, digitally select out those overlapping areas, and then re-organise them rhythmically. And that was what I submitted.

We were shocked when we won. Because such things have happened to us more than once, I see God as the external agent who resides in us, whose hand moves things beyond our abilities.

I have also felt closer to the person of Christ over the years because of two divine encounters that brought me much comfort and guidance. The first happened when my daughter was very ill, and I saw a vision of Christ and his angel near her. A second vision happened while we were in the midst of a church move, and it was also of Christ but focused on his eyes and feet. Such incidents are uncommon for me, but they were significant enough to make me feel closer to God.

And in the aching heart of a displaced person, I know there is comfort from God. He promises a final, rightful homecoming.

Dawn: Thank you, Boedi.

Website : http://www.boediwidjaja.com